Background

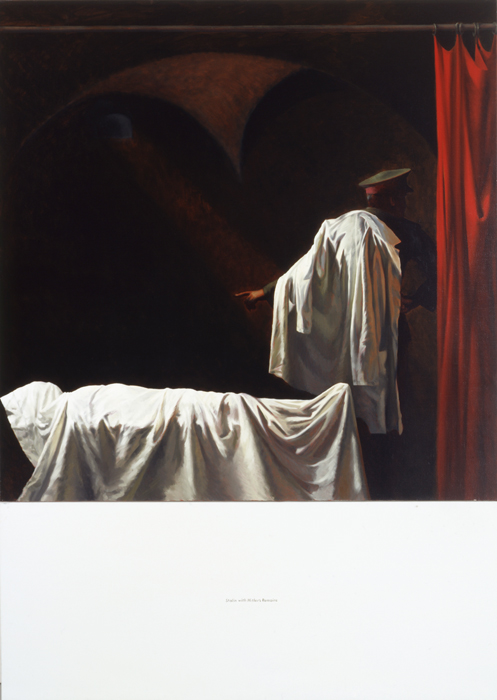

When Russia adopted Christianity in the late 10th century, Russian artists began incorporating influences from Byzantine art and architecture into their own local traditions. Perhaps most notable are the Russian icons, or paintings of saints, with gold backgrounds. Other subject matter, including portraiture, landscapes, and history painting, became more common in the 17th and 18th centuries. The 19th century saw the rise of everyday genre scenes and the graphic arts. Artistic experimentation seemed to explode in the early 20th century, amidst a period of political and social unrest. While some artists drew upon national or folk traditions, others were inspired by artistic developments in Western Europe. Styles ranged from realism to abstraction. Artists blurred the traditional boundaries between different art forms.

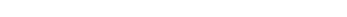

Then, in 1917, when the Russian tsar was deposed and the Bolsheviks seized power, art was mobilized for its propagandistic power. In particular, posters, which could be mass-produced and therefore widely distributed, became an increasingly important medium for building the Communist state. With easy-to-understand and brightly-colored imagery, posters communicated messages about current events, political and social developments, daily life, official culture, and education that even those who were illiterate could comprehend. Poster production came under strict ideological control in 1931. Three years later, in 1934, it was announced that Socialist Realism was to be the official visual language of all the arts on public display. Socialist Realism presented idealized images of life in the Soviet Union, images that the government wanted the people to see. Artists who wanted to create other types of art had to do so covertly.

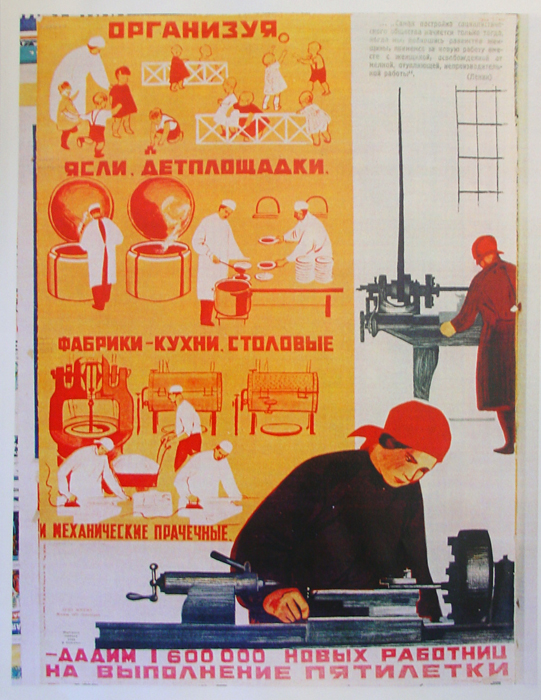

The artists who intentionally went against Socialist Realism from the late 1950s to the late 1980s are known as nonconformist artists. They incorporated a wide range of styles and addressed a variety of subject matter, especially those that were officially taboo. In the 1970s and 1980s two general trends emerged among unofficial artists: Moscow Conceptualism and Sots Art. Moscow Conceptualism is an ironic analysis of Soviet discourse. These artists combined text and imagery, experimented with performance art, photography, and installation, and emphasized documentation. Sots Art is like the Soviet response to Pop Art, with the visual languages of Soviet mass culture and Socialist Realism as the focus of parody and critique. Some architects also challenged official culture. Beginning in the late 1980s, a group of architects created utopian architectural projects on paper, a practice that became known as “Paper Architecture.” With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union, nonconformist and conceptual artists began working more openly and exhibiting internationally.

Questions

What artistic traditions did the artist draw upon? How did s/he transform them? For what reason?

What traditions was the artist challenging and/or rejecting? For what reason?

What messages does the work communicate? How does the visual imagery help to convey these messages? Are these messages visualized in obvious and easy to understand ways, or are the message more subtle and covert?

Who do you think the artist was addressing in his/her art? Why do you think this?

Do you think the artwork communicates an official government message, or at least a message that the government would have approved of? What makes you think this?

Does the artwork critique the government and official culture? If yes, what is being critiqued and how so?

Want to Know More?

Works in the Nasher’s Collection

Duke Libraries’ Russian Posters Collection, 1919-1989 and undated.

Exhibitions at the Nasher Museum

Dissolving the Iron Curtain: Russian Artists in Dialogue with Modernism (Jan. 10 – March 29, 2015)

The Subverted Icon: Images of Power in Soviet Art (1970-1995) (Oct. 13 – Dec. 23, 2012)

Bibliography

Adaptation and Negation of Socialist Realism: Contemporary Soviet Art. Exh. cat. Translated by Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. Ridgefield: Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, 1990.

Andreeva, Ekaterina. Sots Art: Soviet Artists of the 1970s–1980s. Roseville East: Craftsman House, 1995.

Angels of History: Moscow Conceptualism and its Influence. Exh. cat. Antwerp: MuHKA, 2005.

Art in Revolution: Soviet Art and Design since 1917. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1971.

Badovinac, Zdenka, Joseph Backstein, et al. Body and the East: From the 1960s to the Present. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1999.

Balina, Marina, Nancy Condee, and Evgeny Dobrenko, eds. Endquote: Sots-Art Literature and Soviet Grand Style. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2000.

Berlin—Moscow: 1950-2000. Exh. cat. Berlin: Martin Gropius Bau; Moscow: State Tretiakov Gallery, 2004.

Blakesley, Rosalind P., and Margaret Samu, eds. From Realism to the Silver Age: New Studies in Russian Artistic Culture. Essays in Honor of Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier. DeKalb: NIU Press, 2014.

Bown, Matthew Cullerne. Contemporary Russian Art. Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1989.

Brown, Matthew, Matteo Lafranconi, Faina Balakhovskaya, et al. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Paintings, 1920-1970. London: Thames & Hudson, 2012.

Degot, Ekaterina. Contemporary Painting in Russia. Sydney: Craftsman House, 1995.

Dickerman, Leah, ed. Building the Collective: Soviet Graphic Design, 1917–1937. Selections from the Merrill C. Berman Collection. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996.

Dodge, Norton, and Margarita Tupitsyn. Apt Art: Moscow Vanguard in the ‘80s. Washington, D.C.: Washington Project for the Arts, 1985.

Forbidden Art: The Postwar Russian Avant-Garde. New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 1998.

Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s. Exh. cat. Flushing: Queens Museum of Art, 1999.

Goodman, Susan Tumarkin, ed. Russian Jewish Artists in a Century of Change, 1890–1990. Exh. cat. New York: Jewish Museum, 1995.

Gray, Camilla. The Russian Experiment in Art, 1863-1922. Revised and updated by Marian Burleigh-Motley. London: Thames & Hudson, 1986.

Groĭs, Boris. History Becomes Form: Moscow Conceptualism. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2010.

Hoptman, Laura and Tomáš Pospiszyl, eds. Primary Documents: A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art since the 1950s. Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2002.

Jackson, Matthew Jesse. The Experimental Group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceputalism, Soviet Avant-Gardes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Kachurin, Pamela. Making Modernism Soviet: The Russian Avant-Garde in the Early Soviet Era, 1918-1928. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2013.

Neumaier, Diane, ed. Beyond Memory: Soviet Nonconformist Photography and Photo-Related Works of Art. Exh. cat. New Brunswick and London: The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum and Rutgers University Press, 2004.

New Realities in Soviet Art and art Research. Zurich: International Association of Art Critics, 1989.

Paret, Peter, Beth Irwin Lewis, and Paul Paret. Persuasive Images: Posters of War and Revolution from the Hoover Institution Archives. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Petrova, Evgenia, ed. Beyond Figurativism in Russian Art of the Second Half of the 20th Century. St. Petersburg: Russian Museum; Bad Breisig: Palace Editions, 2014.

Petrova, Evgenia, ed. Soviet Myth: Works from the Collection of the Russian Museum. St. Petersberg: Palace Editions, Russian Museum, 2014.

Petrova, Evgenia, ed. Times of Change: Art in the Soviet Union, 1960-1985. The State Russian Museum with The Ekaterina Cultural Foundation. Bad Breisig: Palace Editions, 2006.

Roberts, Norma, ed. The Quest for Self-Expression: Painting in Moscow and Leningrad, 1965–1990. Exh. cat. Columbus: Columbus Museum of Art, 1990.

Rosenfeld, Alla, ed. Defining Russian Graphic Arts, 1898–1934. New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press and the Zimmerli Art Museum, 1999.

Rosenfeld, Alla, and Norton T. Dodge, eds. From Gulag to Glasnost: Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1995.

Rosenfeld, Alla, ed. Moscow Conceptualism in Context. New Brunswick: Zimmerli Art Museum; Munich: Prestel, 2011.

Rosenfeld, Alla and Norton T. Dodge. Nonconformist Art: the Soviet experience, 1956-1986: the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection, the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1995.

Ross, David, ed. Between Spring and Summer: Soviet Conceptual Art in the Era of Late Communism. Exh. cat. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1990.

Samizdat: Alternative Culture in Central and Eastern Europe: 1960s to 1980s. Bremen: Edition Temmen, 2000.

Sobol Levent, Nina. Healthy Spirit in a Healthy Body: Representations of the Sports Body in Soviet Art of the 1920s and 1930s. New York: P. Lang, 2004.

Tupitsyn, Margarita. Margins of Soviet Art: Socialist Realism to the Present. Milan: Giancarlo Politi Editore, 1989.

White, Stephen. The Bolshevik Poster. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.