Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now

August 29, 2019 – January 12, 2020

The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University would like to acknowledge the Coharie, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Haliwa-Saponi, Lumbee, Meherrin, Occaneechi Band of the Saponi, Sappony, and Waccamaw Siouan peoples whose lands include what is known today as North Carolina. We recognize those peoples for whom these were ancestral lands as well as the many Indigenous people who live and work in the region today.

“There is no one Indigenous perspective…no one Indigenous story. We are tremendously diverse peoples with tremendously diverse life experiences. We are not frozen in the past, nor are we automatically just like everybody else. That is why it is so important for everyone to share their own story. In revealing their personal truths, they help us all gain a better appreciation for the messy, awesome, fun reality of the world we live in.” –– Wab Kinew (Anishinaabe), Leader of the Manitoba New Democratic Party and Leader of the Opposition in the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba, quoted in Dreaming in Indian: Contemporary Native American Voices, 2016.

All of the artists in this exhibition are Indigenous—Native American, First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. They come from different parts of what is now known as the United States and Canada and bring many distinctive perspectives, traditions, and contemporary experiences to their art. With this guide, we invite you to explore, learn, and converse as you think about the artists and their works, and what it means to have a new understanding of Indigenous—and contemporary—art.

Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now takes its title from a series of sculptures that artist Brian Jungen made between 1998 and 2003. His Prototypes for New Understanding take consumer items like Nike Air Jordans and transform them into sculptures that reference Indigenous Northwest Coast masks. Jungen’s sculptures call attention to the ways stereotypical images in popular culture shape the dominant culture’s understanding of Indigenous peoples.

Content for “A Conversation” is also available as a small publication within the galleries of Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now. Content for “A Conversation” was developed by the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, and adapted for the exhibition’s presentation at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

Somebody needs to paint the Indian differently because it is a subject matter that is probably the world’s worst cliché, at least in this country.

Fritz Scholder

The common image of a stern man with braids and a feather in his hair oversimplifies distinctions of different cultures and tribes, as if they can be defined in a single image.

Today, there are more than 570 federally recognized Native tribes in the United States. In Canada, there are more than 600 recognized First Nations, Inuit, and Métis governments or bands. Although the term “Indigenous” is used to describe all of these groups, each has their own distinct culture. In the labels for this exhibition, each artist is identified by a tribal affiliation (below their name). As sovereign nations, the right to self-determination is an important aspect of contemporary Indigenous life.

There is no one way to be a Native artist.

Kathleen Ash-Milby (Navajo), associate curator, National Museum of the American Indian.

Kay WalkingStick’s approach to painting was informed by the styles of art prevalent in New York in the 1960s and 1970s. Her two paintings build on Minimalism—a form of abstract art typified by artworks composed of simple geometric shapes.

WalkingStick uses geometric shapes, but she adds Indigenous meaning to the works through their titles, which protest against the diminished status endured by Indigenous people and refer to a racial slur commonly used at the time.

In Artifact Piece, Luna critiqued the way Native cultures are often depicted in museums by installing himself as an object on display at the San Diego Museum of Man. Luna borrowed familiar exhibition practices from anthropology and natural history museums and created labels with identifying information, such as the cause of various scars on his body.

Nearby, Luna created a case with personal items like rock-and-roll records. He poked fun at how Indigenous peoples are presented as artifacts of the past and countered this false narrative with his own contemporary reality. He emphasized that notion with his own living, breathing body.

While some live on reservations (or reserves, as they are called in Canada), others have only experienced urban life. In fact, many Indigenous communities do not have reservations. Edward Poitras addresses life both in urban spaces and on reserves in his artwork Offensive/Defensive.

The photographs document a land transposition in which Poitras swapped a strip of resilient prairie grass taken from his home on the Gordon First Nation reserve, Saskatoon, Canada, with pampered urban grass from the nearby Mendel Art Gallery lawn. While the grass from the reserve turned green and grew, the lawn that was moved to the reserve withered and died. These photographs show how the land served as a marker for the inequality and mistreatment of Indigenous peoples, but also as a symbol of resilience.

In his History is Painted by the Victors, Monkman based the landscape on a painting by Albert Bierstadt from the 1800s. Bierstadt’s vision of the landscape was pristine and unpopulated, as if open and available for European-American settlement.

This visually represents the idea of Manifest Destiny, the belief that it was virtuous and inevitable for white settlers to expand across North America. In reality, the American West was already populated by millions of Indigenous peoples.

The settlers’ expansion led to government policies of annihilation, assimilation, and widespread removal of Indigenous peoples from their lands. Monkman tells the story from the Indigenous perspective, questioning the dominant narrative.

I can still hold true to traditional roots in terms of my materials, my process, but also have the final product be reflective of my personal story as a contemporary young woman growing up both on a reservation and also in urban setting in the city.

Melissa Cody

The terms “traditional” and “contemporary” are complicated and carry different meanings. “Contemporary” can evoke a radical style, or denote the time period of today. “Traditional” can refer to techniques or materials used by a culture over generations. It is important to remember that techniques that might seem unchanged over time are also rooted in adaptation and change.

Cody grew up on a Navajo Reservation in Arizona, and is a specialist in the Germantown Revival style of weaving. Germantown weaving dates to the 1860s, an era when the US government forced the Navajo to migrate and be interned in New Mexico. The government supplied yarn produced in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Navajo weavers incorporated the contemporary material into their style, which is characterized by vibrant color and diamond forms.

I love taking what the white community does or says,” Smith said, “and then recreating it and giving it a whole new meaning—that’s Indian humor when you turn it around.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Quick-to-See Smith has long used humor in her art to prompt the viewer to reconsider notions of Euro-American cultural and racial authority, as well as the historical and current policies and attitudes toward Indigenous cultures.

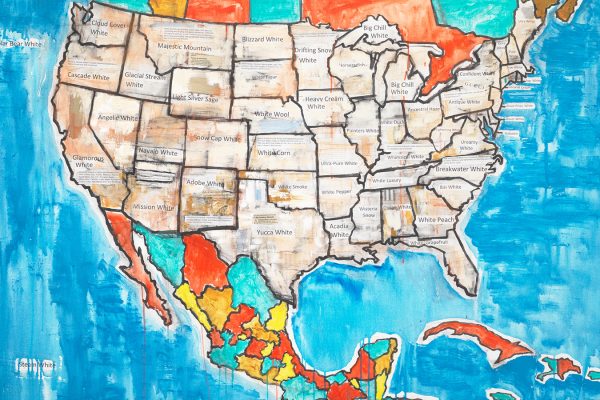

In Fifty Shades of White Quick-to-See Smith presents a conventional map of the United States in varying shades of white paint, which contrasts with the multi-colored blocks of neighboring countries. Instead of labeling each state with its name, the artist inserts descriptive names of various white paints carried by hardware store brands, such as “White Peach” for Georgia and “White Corn” for Kansas. In doing so Quick-to-See Smith humorously challenges the colonial narrative of Manifest Destiny, the belief that the spread of Euro-American culture across the continent was inevitable.

There is a long and violent history in North America of denying Indigenous peoples sovereignty over their own lives and land. For example, the Oceti Sakowin Camp, where the above image was created, was a 2016 gathering of Indigenous peoples and allies coming together to halt the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. A primary issue at play was the need to recognize the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s rights as a sovereign nation with existing treaties that protect their land and community. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, located just south of the intended pipeline, sued the federal government for failing to consult with them before construction began, which threatened to contaminate an important water source for the community.

Cannupa Hanska Luger, who was born on the Standing Rock Reservation, made mirror shields for water protectors (protestors of the pipeline) to hold while serving on the front lines at the Oceti Sakowin Camp. Though the resistance did not result in halting the pipeline, it drew considerable national and international attention, and plays a critical role today in conversations about Indigenous sovereignty, including land and water rights.