The hope of a fresh possibility and to collectively imagine the futures we want to manifest into being with each election cycle and beyond.

Xuxa Rodríguez, Patsy R. and Raymond D. Nasher Curator of Contemporary Art

Listen and Subscribe

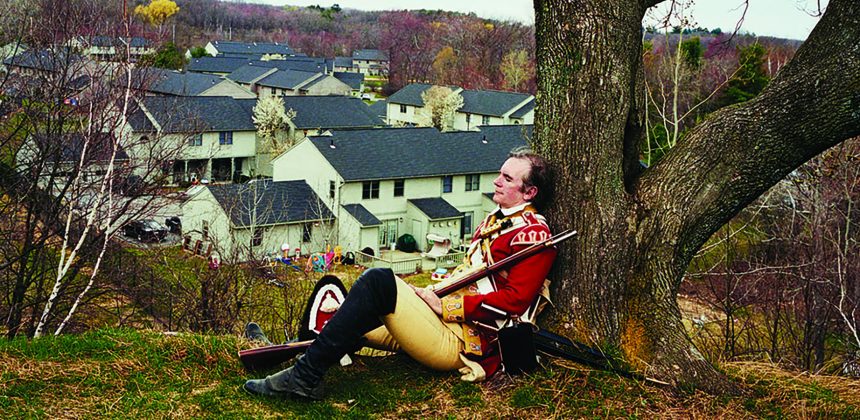

By dawn’s early light reflects on the historical context against which these Acts came into being: the U.S. Constitution’s Preamble and the rights outlined in the First, Second, and Fourteenth Amendments. Each gallery features selections from the Nasher’s permanent collection that speak to these documents, questioning what it means to form a nation, to have a right to assemble, to own weapons, to pursue the American dream, and to define who “we the people” are.

Listen on

Transcript

Hi y’all! I’m Xuxa Rodríguez and I’m the Patsy R. and Raymond D. Nasher Curator of Contemporary Art here at The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. I was formerly the Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at Crystal Bridges and The Momentary in Bentonville, Arkansas. The show we’re going to talk about today is By dawn’s early light which is my first show at the museum.

The show is looking at, and reflecting on, the 60th anniversaries of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Those two acts transformed life in the U.S. for so many marginalized individuals.

Historically this work is the culmination of a century of work by activists and advocates.

So it’s really reflecting on the historical context against which the acts came into being, which is the U.S. Constitution’s Preamble and the rights outlined in the first, second and 14th amendments. Each gallery features selections from the Nasher’s permanent collection that speak to the documents–questioning “what does it mean to form a nation?’ “to have a right to assemble,” “to own weapons,” “to pursue the American dream,” and “to define who ‘We the People’ are.”

Ultimately, the exhibition asks us, “what do we hold dear and how are we using our voices to protect those things when we go to the polls in each election?”

The title of the exhibition is not just a quotation from the national anthem but it’s also this metaphor for the start of an early day–a new day–the hope of a fresh possibility and to collectively imagine the futures we want to manifest into being with each election cycle and beyond.

Thinking back to recent events such as the repeal of Roe v. Wade, things like the historic Muslim ban and other things that have happened that have spoken against what we fought for for so long, which is to expand equal rights and opportunities for all, it felt really critical to take a moment and bring together works that showed the struggle that folks have collectively put into ensuring that we could just live our lives, essentially. Wake up every day and go about our business without fear of recrimination or hatefulness thrown upon us or being limited in the full expression of our lives.

I don’t think the show is going to be revolutionary in terms of a game changer, but I hope what it inspires is a moment of pausing and reflecting and thinking about what’s really important and what are we going to gather around together and keep fighting for.

It’s kind of hard as a curator to say which is your favorite work out of anything really that you’re collecting and or caring for, but I think within this show one of the works that really stands out to me is Adrián Balseca’s Supradigm. It’s a car with a stack of sugar bags above it. I love that work because it’s pretty magical to walk into the room and see this tiny microcar that actually represents, historically, if I’m remembering correctly, the first electric car in the U.S. It was sprung out of desperate need with the oil crisis of the ’60s and ’70s–and we rallied around and found a solution very quickly. To me it represents both this moment of when times are tough we can find a solution.

Balseca is a fascinating and brilliant artist because he also puts the sugar bags on top–the sugar bags, you know, reference Florida and Cuba and the U.S. and the embargo and this reflection on international relations and our moments where we haven’t been exactly the most beautiful to each other. To me the word “Supradigm” suggests a paradigm and Supremacy or a Supra Paradigm, above all, and really reflecting on this idea of a nation as a construct and the shakiness of it and and all it entails. It also includes violence via colonialism, invasions and extraction of materials.

Colonialism is a thread that runs throughout the exhibition in relationship to the formation of the nation. I think of Edward Said’s work on The Nation himself in exile–Palestinian exile–reflecting on the violence of a nation.

To form a nation means to close off others under the banner of this singular imagined whole that doesn’t necessarily exist in space–it’s a construct via paper, legislation, discussion–it’s not actually on the ground, as it were. Also Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities also talks about the nation as a space or even you know the state as a space that exists only on paper and in our collective imaginations and not as a real thing that we can walk into physically [laughs].

I think a lot of folks here cross between North Carolina and Virginia or North Carolina and South Carolina and like the cross is marked by the sign on the highway, but when you look on the ground there’s not actually a line that says “this dirt here is North Carolina and that dirt there is South Carolina” it’s just a sign that says like you’ve now entered this. Or on the Google Maps or the, if folks still use the Garmin Maps, the little dotted line on the digital image, but it’s not in the landscape. So Said and Anderson are both calling attention to the fact that these things only exist and are imaginary, but they’re also exclusionary and if we keep reinforcing them what that means is we’re letting folks out and so there’s an inherent violence there with it not being a nation or a state not being for everyone–it’s for those who kind of collectively agree that we hold it in our minds that it’s real.

I saw Supradigm digitally via images online of the collection and images online of when it was exhibited in a show at Denver Art Museum and interviews with Balseca where the car’s captured as part of the b-roll. So I hadn’t actually seen it in person, but I got a good sense of the scale and what it would feel like in space from that documentation which speaks to the importance of documenting your work.

And walking here into the space for the first time of the gallery seeing the car on these little individual rolling platforms for each wheel in the space was really magical and fantastic because it almost looked larger-than-life because it was suspended almost up in the air and then once we figured out exactly where we wanted the car to live and seeing it on the ground and really feeling its weight in the space–doubled also by the weight on the car from the bags of the sugar–and walking around the car and seeing like how very small this little machine is and yet how powerful it was because it resolved a lot for folks in need at the moment while also showing human ingenuity and being able to problem solve on a very short timeline.

I think there are many works in the exhibition that folks can walk by and not consider because of how small they are or sometimes how beautiful they are. I’m thinking of Scherezade García’s beautiful painting that is rapturous because of the brush strokes to me. And you can kind of like gloss over what she’s representing which is this mass exile by sea of folks historically from the Caribbean to the U.S. and you know who’s lost in that narrative because of the need to escape dictatorships and other experiences of governmental and national instability.

Another work that I think that’s easy to walk by is Sarah Sudhoff’s New Spelling which is a video work that features her children engaging in this very seemingly everyday spelling drill. It’s a scene that’s very familiar, I think, to a lot of folks who themselves have had spelling drill homework and kind of going with a buddy back and forth you know can you spell this your buddy’s like that’s wrong or that’s correct and the annoyance of the task you’re just doing this repeating and spelling and repeating and spelling and repeating and spelling until it’s embodied within oneself. But in that work if you spend a moment with it what they spelling is actually really horrific. It’s words related to gun violence in the U.S. You know you see these two children that are kind of annoyed with each other because they have to do homework right so like the the gravity of the situation is so mundane in the experience that it’s horrifying–especially with the Surgeon General’s recent declaration of gun violence as a public health crisis. And that work is one that I think folks will walk by you know, but if you spend a little time with it’ll scare you and if you don’t spend a little time with it it could kind of seem like “oh, it’s just kids spelling.”

In terms of the biggest highlight that I hope visitors take away from the show is that they walk through and they reach that last section titled We the People and really gather what it’s trying to convey which is the nation that we’re living within that’s kind of reflected upon within the show is very diverse. It has folks of all ages and walks of life, of all racial ethnic backgrounds, of all different class and ability backgrounds as well. And I hope it sits with folks that they’re part of that story–the folks in those images and the folks potentially also with them in the gallery space who were also walking through the show are also their neighbors as well and their fellow citizens and residents and that they get this sense and hopefully inspiration that what we’re all fighting for is each other and each other’s livelihoods and well-beings. That’s my hope. I don’t know if that’s what folks will walk away with, but, you know, one can have little dreams.

Nasher Podcast Team

J Caldwell, Multi-Media Public Relations Specialist

Kourtney Diggs, Multi-Media Production Assistant