The photographs are the remnants and they can create catalysts, but they also are, in many ways, in memorium to what we have left.

David Benjamin Sherry, artist

Listen and Subscribe

Second Nature: Photography in the Age of the Anthropocene is the first major exhibition to examine the Anthropocene through the lens of contemporary photography.

Listen on

it's really important for the viewer to come forward and meet me halfway; I'm showing you my soul, my bloodline, where I come from, my history.

Hayley Millar Baker, artist

Artist Bios

David Benjamin Sherry (Born In Stony Brook, New York, 1981) creates vast, large-format landscapes of the West that recall those by nineteenth- and twentieth-century predecessors such as Carleton Watkins and Ansel Adams. Sherry is a self-described “nostalgic futurist,” who simultaneously references the past and looks toward the future. He sees his presence as a queer man making images in rugged and rural terrain as a performative process. By embracing this aspect of his identity, he is able to present an alternate to the heteronormative precedence set for our understanding of ecologies and environmentalism—thus using his queer identity as a strategy for conservation. Working in large-scale analog film processes and more recently in painting, Sherry’s sweeping monochromatic views are both seductive and cautionary, reinvigorating the American western landscape tradition by underscoring the fragility and vulnerability of these lands. He has written, “These photographs represent resistance, self-determination, and optimism—core American values—imperiled as the land itself.”

• • •

Hayley Millar Baker (Gunditjmara And Djabwurrung, Born In Melbourne, Australia, 1990) was a painter for a decade before transitioning to photography, film, and collage. She uses these media to interrogate and abstract stories founded on southeastern Aboriginal existence—drawing from her Gunditjmara bloodline and examining the roles our identities play in translating and conveying our experiences. The meticulous layering of her imagery creates histories and landscapes in which disparate times, cultures, and transformations coexist. Millar Baker’s stratified, elusory imagery emphasizes temporal fluidity and connection to identity. Her practice examines how memory and identity are neither linear nor concrete and highlights Indigenous experiences of place, time, storytelling, and the intergenerational passing down of that knowledge.

Additional Second Nature artist bios by thematic section

Transcript

Marshall Price: Welcome to Second Nature a collaborative podcast produced by the organizers and host venues for the exhibition Second Nature: Photography in the Age of the Anthropocene. I’m Marshall Price Chief Curator and Nancy A. Nasher and David J. Haemisegger Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and one of the curators of the exhibition I’m joined by my co-curator Jessica May.

Jessica May: Hi Marshall. I’m Jessica May I’m the Executive Director of the Kemper Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri our exhibition presents the first major photographic survey examining the anthropocene thesis through the lens of global contemporary photography. The anthropocene is generally defined as a proposed geological epoch in which humanity has had an impact on the global climate. Over the course of this project however we’ve come to understand the anthropocene not as one singular narrative, but a diverse and complex web of relationships between and among humanity, industry and ecology, the depths of which are continually being discovered.

MP: We conceived of this podcast as a way to broaden our audience for those who may not be able to see the exhibition as well as provide a forum in which we can continue to discuss topics relevant to art and the anthropocene in broadly intersectional and interdisciplinary ways. As Second Nature makes its way across North America the Nasher Museum and the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art along with our host partners the Cantor Art Center at Stanford and the Anchorage Museum Alaska will release episodes that include discussions with artists, curators, scholars, scientists and others who engage with aspects of the anthropocene in their work.

JM: Here we are today with two of the artists in the extraordinary exhibition Second Nature which just opened last night and I think Marshall and I are just so honored to be with David Benjamin Sherry and Hayley Millar Baker and ready for an open-ended conversation about your work in the show and your relationship more broadly to this show and the way that it proposes a dialogue about what the anthropocene is and can be and needs to be in our lives. So I wonder if we might start with you Hayley talking just a little bit about the work that you have in the show and how it fits in with yours.

Hayley Millar Baker: Thank you. My name’s Hayley Millar Baker and I’m a Gunditjmara, Djabwurrung woman based in Melbourne, Australia. The work that I have in this show is from a series called Toongkateeyt which, in my language, means “tomorrow” but it references the past, the present and the future and really references the landscape as a living identity and this living portrait. It’s a photographic collage made up of literally hundreds of photographs cut out and digitally stitched together to represent the landscape’s portrait over four or five generations of women in my family who have connections and lived off our Aboriginal land back in Australia. It goes over 75,000 years but in this case I’ve spoken about the direct generations that were around right before the colonization began and then as the colonization progressed throughout the area to nowadays where some parts of the land have been left and fallen apart from colonization and the rebuilding and renourishment of the land’s identity are now coming back and being cared for. So this series is really complex, but the way that I look at it again is as a portrait of the landscape and of multi-generational experiences and that, I feel, is quite a common approach to take in Australia for Aboriginal people. For example, just off the top of my head to add here, portrait prizes, painting portrait prizes in in Australia often has aboriginal artists submitting paintings of their country because it’s a portrait of a being it’s a living thing that grows and has all these things happen to it over time.

Installation view of Even if the race is fated to disappear 2 (Peeneeyt Meerreeng / Before, Now, Tomorrow) and Even if the race is fated to disappear 7 (Peeneeyt Meerreeng / Before, Now, Tomorrow) (both on left) by artist Hayley Millar Baker. Photo by Brian Quinby.

MP: And with us also is David Benjamin Sherry. David, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the work in the show that you have and maybe the series from which it comes

David Benjamin Sherry: Hi, I’m happy to be here. Thanks for including me in the exhibition, it’s been wonderful to meet everyone and to be here to see all this work together my work that’s in the exhibition is from a series called American Monuments. The project began as a further investigation into how the American West has been documented and trying to shift a perspective of where we’re at with the environment specifically the American West. The piece that’s in the show is from an area in Southern Utah which is called Bears Ears National Monument. I began photographing Bears Ears pretty much right as Trump…President or just Trump was elected…President Trump…I hate saying “President Trump” it’s awkward. When Trump was elected one of the first things he did was to immediately go into a lot of American wilderness places specifically national monuments which don’t have the same protections as our national park system. A lot of these national monuments are protected in some ways but he found some loophole to remove them from their protected status with the idea to develop oil, gas and coal extraction to put energy back into American soil. The funny thing is Bears Ears is a really kind of political complicated place because of the presidents that came before Trump so a lot of it is back and forth it’s I think it’s Bill Clinton recognized the area and then Obama made this region as big as he possibly could and created a really large boundary of this area as protected. So as soon as Trump came into office that was the first thing he did was as kind of a “fuck you” to Obama…can I curse?

JM: I think you can curse on his podcast.

DBS: I went there immediately. I had been photographing the area for many many years it is a sacred space for Native Americans and also a convergence of four different tribal unions that have lived and breathed this area. I just was traveling through and spent a lot of days and months living in my car and camping and photographing through the area for years not even knowing where I was. I just remember it being this wilderness like there’s no roads, basically, there’s no guides, there’s no information. I knew that the area had like a lot of historical importance but there’s something to be said about hiking through the wilderness and coming across petroglyphs that are ancient and looking up and seeing. Eventually I found guides and I worked with guides–local guides–and they would show me specific petroglyphs through binoculars like really far away but things are kind of left I mean there’s a road that runs through the whole thing and it’s the only development that’s kind of been there. I photographed there as in many ways…I use an 8×10 film camera and…the reason I use that camera is to kind of go into the historical canon of photography conceptually that was part of how I wanted to shake things up. That work started many many years ago about 15 years ago as documenting the West through a different set of eyes. As a queer person I found myself traveling through the West and being made aware of my identity over and over from simple things like being in a campground next to families and being like alone person and people constantly asking “where’s your partner, where’s your wife?”–where’s your wife mostly–’where’s your kids?” “why are you alone?” Those questions would resonate as I’d hike for miles and miles and miles.I thought a lot about my identity and at the same time was into this idea of preservation of what’s left in our country and what’s been photographed so many times and has been totally romanticized and, in this era of ecological collapse, what does it mean to re-photograph some of these places and offer a new perspective.

Installation view of Valley of the Gods II, Bears Ears National Monument, Utah by artist David Benjamin Sherry (right). Photo by Brian Quinby.

My photograph in the show is the largest possible size I could make analog. I shoot 8×10 film and print analog color photographs and I manipulate the color in the dark room. And that’s an alternative process that I found when I began making this work about 15 years ago and the color is representational of many things, but, for me, it adds this other layer of connectivity to the place and the color is extremely saturated and really vibrant so it brings you into the work and you recognize the color first. I found and that draws you in and then you’re pulled in to witness something really beautiful which is our land that we are on and to have that moment and to be humbled by this epic, grand landscape, but also the color removes it from reality and kind of helps, I think, the viewer engage with nature differently. That’s how I found myself in this realm it’s a trifecta of environmental concerns, history of photography, identity and I guess preservation…that’s four things.

JM: For viewers who haven’t seen the show yet what’s amazing is you walk in and both of your work’s have a very interesting, I would say, palette and your’s, David, has this sort of surprising chemical blue I would call it, beautiful, but also rooted, I think, in 20th century beach imagery, you know, beach color. Hayley you’ve talked really movingly about the fact that you work in black and white and, of course, black and white is now a choice, it’s not a necessity and, in fact, it’s a little bit of a counterintuitive choice. Maybe before we talk about the show further maybe would you talk a little bit about your use of black and white?

HMB: I was just thinking, as you were saying, David, I do the opposite. I think in Australia with our landscape–the traditional landscape paintings that the settlers did when they first came over, because they came from Europe–they didn’t have the same color greens as the greens that we see in the bush within Australia–it’s all very European greens. So when you look at those paintings that they used as documentation to send back to England to say “this is what the landscape is this is what it looks like”…it doesn’t! it doesn’t look that way. That’s just an added extra layer into I guess the history of landscape when looking at these works in particular but I shot in color–I shoot all of my work in color–I have a medium format camera that I shoot with but I also always take a digital camera with me just in case to back myself up, because you can never really trust film. So, shoot everything in color on film and then I reduce it to black and white, but it’s not just a matter of desaturating it’s a process to try and marry all of the images up together but also create a lot of conflict in those landscapes. Conflict in terms of light and shadow and the contrast and perspective of each of the images, because it’s meant to be jagged and a little bit unnerving when looking at it like from afar. You do see it, it looks like “what’s going on here?” but once you go up and then you start to notice you know all of those sharp cuts and the shadows and the blacks. It’s quite ‘stabby,’ that’s the first word that comes to my head. It hits you. And I’ve talked about the idea of it also looking like photocopies–photocopies of photocopies of photocopies. Now they don’t really look like that but they reference that type of flatness in these collages. In my collage period, which continues, but I would say that the more complex collages from 2016 to 2020 I really looked for this flatness because the amount of complexities and deep histories and knowledges and experiences they have to be sharp and stabby. I do look at them when they’re in color when I’m building them and things just get so lost. It becomes very lost and adds this extra part of it that I don’t think adds to the viewers experience of the work.

Once it’s reduced you can take it to–I know that it’s very specifically about my country in Victoria–but you could reference it to a lot of other indigenous or black or colored areas throughout the world. So color as well in film has a lot of reference to a lot of different generations and eras like when brown finally came in not all that long ago in film or you know the hand coloring of film. To sort of skip around what era these stories and photographs might come from–because I do mix archival imagery with my own imagery–to skip around all of that and to make it this eternal churning circle of history and present and future, the black and white serves its purpose that way

MP: One of the reasons why you know we were interested in having the conversation with both of you are these formal sort of affinities that the work has but, as we discussed earlier they also have a strong conceptual affinity with one another in the way that they both push against sort of larger overarching narratives and, David, maybe you could talk a little bit about how your work functions in that way.

DBS: Immediately when I saw your work I also I thought of the textural element maybe when you’re saying stabby it’s…because there’s so much texture of Earth throughout the photographs and they’re so textural, the clarity, the sharpness contrast. That’s something that I think is really exciting especially in the piece that’s in the show that I got to see because I haven’t seen my own work. It’s rare that I get to see my own work at this size, it’s a mural print in all of its glory in a museum space and it feels really nice to see it and to see that parallel eye level where you’re looking at my photograph it’s all about this texture and you kind of get lost in the crevices and rocks and the contrast. That’s part of the reason that I love making them so large is that when you’re standing in front of something so big and has such a presence you kind of get lost in that and you don’t get to really like have this still quiet meditative moment where you can just fall into the texture of a rock and it’s so ancient and has seen so much and has been will be here way past us and has been here way before us that just doesn’t really answer your question but I felt like that was something I was thinking about with our work and something that really connects that. Can you repeat your question, Marshall?

MP: We can take it in any direction, really, but just the way in which it pushes against sort of larger narratives at play.

DBS: I love historical photography, I have a huge collection of books of photography, I studied photography, I my Master’s in photography and I’ve always kind of also been really against photography when I was in graduate school. I remember I got ‘congratulations’ at the end for going against the grain of what I was at Yale for their MFA program which it goes through many phases. When I was there was so much coming out of this staged, large format photographic from life kind of stuff. I was interested in breaking the color dark room because everybody was going digital so I was like there’s things we can do in the analogue film process that haven’t been done yet and that’s kind of how I found my color–subject matter. I was coming out, so a lot of the work was about me and my coming out and kind of how I was creating some type of queer mysticism which I think is still a big part of my work and that’s kind of where my work was born. But my approach to landscape is it wasn’t really what I intended to do when I was graduating from my Master’s at Yale. I lost my closest friend tragically and it was the hardest thing I’d ever really experienced up until I was 27 and I thought coming out was really hard, but this friend was the vehicle that helped me do that. Her name is Lily and Lily changed my life and right after she had passed it was kind of her thesis time and I didn’t know what to do with myself I felt like the lowest I’ve ever felt and I went on my first trip out West and brought a 4×5 camera and found myself understanding grief and life and this all-encompassing circle of life.

Out West it was the first time I’d made landscape photographs that were really meaningful to me, but they came from a place of grief and they had nothing to do with, at that point, the history of photography, the history of art–I was living I was finding my life again without this person through my artwork and then I married that with this kind of color thing that I developed in the dark room. What came about by chance, by this terrible thing that happened, I found myself retracing my forebears footsteps through the American West in the next 15 years and finding all these problems and all these notions of manifest destiny and everything that is tied to the American West and how the world looks at the American West through these first photographs and paintings. I felt like, as a queer person, retracing these footsteps there was something really empowering about that. I felt probably five or six years into it I started talking about that like, yeah, actually I don’t know many other queer landscape photographers that are retracing these steps and trying to understand the history of photography through landscape. I always felt like very much outside of the landscape canon weirdly because I didn’t come from it trying to document the West to show people what Yosemite looks like, it was beyond that, it was like the key to our survival as a species is hidden in those waterfalls and that’s what kept me keeps me going. The photographs are bigger than just the place, it’s about survival and about all these complicated things that landscape in 2024 bring up–colonialism and environmentalism, identity politics and the end also of an analogue film process that was a huge part of my impetus to kind of keep it going and find some new ground within that.

I felt like I was a really angsty kind of punk kid that went through a lot of different phases in my life, but I always kind of feel like that in photography as well because I’m using this historical camera–and that was my way to kind of wedge myself in there–to help all of us understand why these problems exist in our country, in landscape and in the world. I had the knowledge of the history of landscape but I wasn’t trying to even add to it because it’s all been done, we all have phones everybody loves to be outdoors and I mean in the last five years especially like you can’t even get into a campground anywhere because it’s so busy which has helped me kind of pull back. I’m grateful that I got to make a big chunk of my American Monuments work and stuff before that kind of outdoor craze. I’m so glad that the youth and everybody are kind of trying to be outdoors, but there’s respect and understanding that you have to kind of gain through, hopefully, this show. Things like this show and environmentalists talking about these spaces being protected and what does that mean and how we tread lightly through these places, or not, most people not, and most people leaving their trash behind which is a whole other problem, but these are the things that I feel like as a landscape photographer or artist–I consider myself landscape artist–these are the things you kind of bear witness to through the photographs or at least I do.

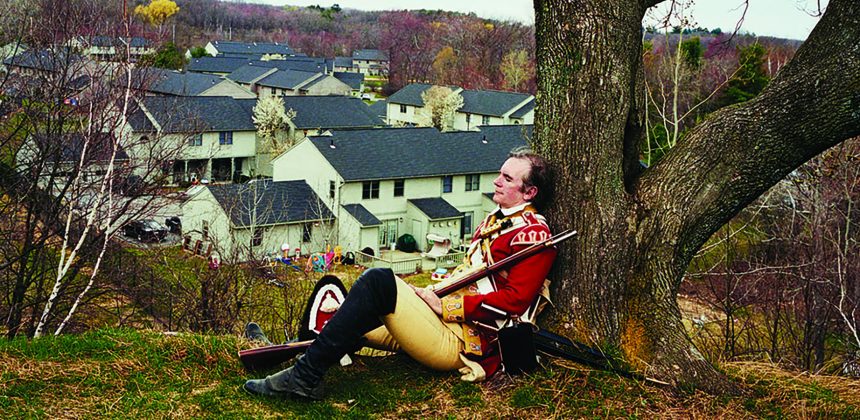

Artist David Benjamin Sherry. Photo by J Caldwell.

I feel like a lot of it is watching this happen and the photographs are the remnants and they can create catalysts but they also are in many ways in memorium to what we have left.

HMB: I feel like it’s so beautiful hearing you say that you’ve printed this big rock that people can just get lost into the texture in comparison to my work that’s in the show that was created during my second year of my Master’s of Fine Arts in Melbourne where I was up against a whole cohort that didn’t understand or want to understand my identity. And so it became almost like a teaching resource–like I got pushed into this. It was like ‘get as much in as I can.’ Australia’s only been colonized for like 270-something years now; get those years in but then also still have a side that has some nourishment to it. So, it became working in a way that sort of Hieronymus Bosch [Dutch painter -ed.] worked with his paintings in that you know they’re almost like little “I spys” but every piece is important and every single element is telling this story, but when you look at it the stories are sometimes violent, sometimes happy, sometimes messy, it’s just this big image of what looks like organized chaos, in a way. And this is actually my first works that deal with the landscape, because the works that came before this were a series called I’m The Captain Now where I was reauthoring or taking back the narrative of what 1960s Australia was through like the white Australian policy and segregation and all of those horrible things that were going on at the time. But stepping into landscape I felt that it was almost like a freedom that comes with it–I’m not putting myself on the line as a person, but I’m using the landscape as a character and no one can rebut that. You can’t talk back to that and you can’t argue with that because the landscape is what it is and it is scarred and those scars remain and whether you water it or grow it back or whatever it permanently tells this story that you can’t argue with. Stepping into the landscape I sort of leveraged on that and lent on that for a good while until I got to a point–which goes back to your showing us a huge rock in a huge print–is that I can be bold and focus on this one beautiful thing.

The landscape will always be there and there will always be people looking after the landscape and photographing the landscape and I’ve shown these stories through my identity and the way that I see it through my eyes and my family has seen it, but stepping out of that I am also the landscape. I carry that within me and within my bloodline and bit by bit over time, from creating this series, the landscape has become more abstracted and more abstracted.

To going back to talking about landscapes portraits and portraits as landscapes, a series that I did recently which is called In Life, In Death, from this year, they’re self-portraits but the landscape of my ancestry and identity and cultural practices all exist within the portrait so whilst there are no physical remnants of a leaf or a rock or that landscape I am the remnant of the landscape. It’s never really, for me, detached, but I have been able to find bigger, more meditative and monumental ways to express that in a way that nourishes me as a human being coming from those histories.

DBS: That makes a lot of sense and thinking about the piece that’s in the show because I feel like all of those layers kind of tell the story and hearing you speak about the work it unravels so much and there’s so many layers and physical archival pictures that you’re putting together and creating this…

HMB: It’s like a big net that I’m slowly unpicking you know that we’ve been caught in–Aboriginal people have been caught in–for you know 270-something years and unpicking that and just letting it unravel and being okay with that unraveling and being at peace with it…

DBS: …and there’s a freedom maybe in that.

HMB: There’s an absolute freedom but I’m not leaving anything behind it’s just that the representation has become something that is more, like I said, nourishing and healthy and healing and you know beautiful to step forward into such as your rock.

DBS: It’s interesting. I used to make my photographs a lot smaller and I felt like it wasn’t there like there’s something I was still working out through the process of…

HMB: …well, it’s a reflection of ourselves and where we’re at and we’re trying to figure it out and then it’s years later when we come back to it and we see ourselves then…

DBS: …it’s like a mirror anyways. I really like how you were talking about it’s like the internal landscape, let’s say, I mean that’s kind of how you were describing, like your body knows the the landscape it’s inside of you and and I think that’s a really kind of beautiful way to think about how we look at the world.

HMB: Your work is very much a portrait.

DBS: I think it is too and I think it’s so exciting to be in an exhibition of works where ours kind of I think create that almost meditative state for a viewer to kind of get lost in all of these elements that are, at times, textural or…

HMB: …but we’ve done it different ways, totally different ways, but it’s doing the same thing…

DBS: …it is, yeah. It’s really beautiful because there’s other pieces in the show–I’m thinking of like the first piece kind of when you walk in which is the Thomas Struth piece–there is a like a wonder to that piece but there’s something…it’s like a documentary photograph it’s very kind of straightforward in the way it operates, I mean it’s this grand, massive print, so I think we kind of get lost in that, it’s almost lifesize. It’s a really beautiful entryway into the show because the photograph is a photograph of children and parents kneeling and sitting on the floor in front of an aquarium so half of the photograph is pretty much the aquarium the other half is the humans so it just operates so differently in the context of the show where I think it’s just a beautiful entryway into the show because it’s these two worlds–it’s humans and then this artificial, created world of something that is part of what we’re dealing with in the anthropocene. It’s just nice how the works kind of bring you back to the landscape.

HMB: I think that our works are really inviting audiences to come inside…

DBS: …yeah I think so too…

HMB: …and the aquarium image asks us to observe and question where we stand. Our works are quite conceptual, which we’ve spoken about, and it may not seem that way while looking at them–maybe mine does a little bit more because it’s not traditional photography, even though all of the images are traditional photographs–but we’ve got heavy narratives behind it from the land that you’re using and the land that I’m using to even who we are today and we want those people to get lost in these portraits of our souls and sort of find us in there, but also bring themselves forward to me us halfway, if that makes sense.

DBS: I think it is. I like this idea of with these large scale vertical pieces they’re almost life size so you can, yours too, two large vertical pieces, that you can really walk and enter them and it’s really fun to see viewers enter the piece, in many ways, and of it’s a physical experience I guess is what I’m trying to say.

HMB: Scale is so important because scale can change the entire experience. So mine looking up and down and sort of reading it that way and yours you know you go into the landscape it’s like you’re there looking at it because it’s almost hitting peripherals and mine’s hitting peripherals that way [gesturing up and down]. So we’re doing it opposite ways and that’s another trick to get people to get lost in work; there’s so many tricks that you can pull with photography that I love that you can capture people for different reasons and pull them by the heartstrings without them even knowing.

DBS: Exactly! I think it can be really powerful and I feel like through experimentation is like this idea of trickery, I feel like, because I feel like I don’t want to trick people myself, I just want people to feel empathy.

HMB: Not a trick but like a a mechanism to bring someone forward.

DBS: It’s like like a moth to a flame or something.

HMB: Yeah! A trick!

MP: I think both of your work generates a kind of cognitive dissonance that is the lure that people will enter into I think that definitely is the case and, Hayley, your work is very vertical, as you were saying, but there’s also a kind of temporal depth to your work that gives it a spatial locus that is much deeper than simply like a surface or a flat space…

DBS: …it’s almost like we’re going underground looking out your piece. It’s like horizon and then just keeps going down and into the depths.

HMB: Yeah, people people do start at the top and that’s not something that I’d thought about before because there’s just as much interest built into the bottom to climb up and on the second image to the right in the show of my work there is one human character, and I call them characters because it’s a character–it is my mom when she was a baby that was photographed by my grandfather–but this character is seemingly climbing up to go back through those concrete windows to go out into the mountains that are in the distance, but she could also be climbing down to get away from them. They are built bottom and top sort of inways to meet. It’s a lot of different layering of locations of times of day and evening to all come together and then there’s a lot of mirroring as well which is a trick, I guess, [laughs] so people sort of get lost in that as well. People are looking for the joins. I had somebody yesterday saying “I can’t see the joins in this” and it’s like where the images come together, like how you would in a typical collage if you were doing it manually. Those textures sort of bleed together and the repetition of it and it’s another way of causing people to go into like this state of meditation or this you know real softness in the mind and the chest where you’re you just get lost in it one part leads to the next part leads to the next part and then you know the more you find the more the landscape opens up and the narrative unfolds and more is available for you to read. But I don’t think that it’s also necessarily important for the viewer to know the history. Like I was saying, for me, it’s really important for the viewer to come forward and meet me halfway; I’m showing you my soul, my bloodline, where I come from, my history bring yours forward and see where I’ve been see where my family have been. Like sharing the stories between all of the different little elements that are in there and the histories that come with that. From the histories of the rocks being used to escape colonizers during massacres to then being put into slavery to build the rock fences which are quite iconic all through the Southwest Victoria and they go for kilometers and kilometers and kilometers to fence off when the settlers wanted to create their own property lines and fence out people, similar to the movie Rabbit Proof Fence–I’m not sure whether you’ve seen that over here–but that’s creating those rabbit proof fences but really what they were for was Aboriginal proof fences.

Artist Hayley Millar Baker. Photo by J Caldwell.

Then going from the rocks in the fences then to using rocks to build the homes on the Missions or as you would call Reserves you know and then them crumbling down. The stories of the rocks themselves just in the images–each individual rock from each place– that has its whole history. I’ve had people write extensively on my work on the rocks, like theory essays, into the rocks in the work. There’s so much to unpack, but I’ve made the work and I feel like I’ve delivered it to the world and it’s been–I don’t know how long when 2017 was, I’ve lost years from COVID–whenever that was seven years ago and for me the story keeps developing and unfolding as well and, like you, I don’t get to see my work that often but when I do it’s like “oh yeah I forgot that I put that there” because everything’s so hidden. But the interpretation is up to the viewer and then just left-of-field here my favorite–in cinema–my favorite movies–and in literature–are stories that never finish they never give you an ending they’re open-ended. You close the book or you turn the movie off and you’re like “what the hell?” And that’s what I’m offering here there is the chance to go online and do a deeper dive to learn more, there’s layers, it’s whether you want to see it for what it is or whether you want to go a little bit deeper whether you want to Google my name or Google whatever Gunditjmara means. All of that information is there I’ve provided you visual cues and now go forth and see what else, if you’re interested, if not, it’s not my responsibility.

JM: It’s such a sobering and amazing thing to think about a world opening up through a photograph. When we were working on this project one of the things that we talked about early on was thinking about this moment in photographic practice and Marshall I think you were really clear and saying there is a new kind of language, there is a new act and a new approach and I think about the ways in which you know in my own life as well as in my professional life often the history of photography, for me, is about moving past things pretty quickly. But in a way the language or the photographic language as it were, and I know that’s a little bit of a funky way of thinking about it for both of you, is the language of perspective and the personal to be candid which isn’t to take away the power of observation of the world but just to say that there is something in both of your work that holds so true to your own perspectives and your own work. I wonder if you might reflect on that a little bit beyond your work to other either works in the show or how you think that fits in with a narrative of photography now.

HMB: I think there’s two different ways to look at photography–well at least for me–there’s “photography photography” and then there’s “art photography” and I think art photography at the moment is really on the rise. I guess what I mean by art photography is narrative photography compared to documentative photography. The works that we were listening to Anna Lindal talk about and she was saying that she looks at her work as it’s a documentation but then she starts speaking and you very quickly realize this is not documentation, this is her story, this is her narrative and her experience and her interest. I think that we’re inserting ourselves into the story now and because the world is going to go up in flames and everything’s ending and everything’s in a terrible position pretty much everywhere we’ve got things to say and whether we say that directly or as artists we say that visually through our work. I think that’s coming across more so now and everything–not everything–but most things have been discovered most things have been done most things have been said you know now it’s more about the personal and what we can put forward and also what we look for to gain from an artwork. The younger generations that are coming forward whether they’re interested in art or not I think or at least I want them to feel seen or heard or represented in one way or another within my art to gain their own confidence to figure out their place in the world to go forward. I don’t know if that answers your question.

JM: I think it’s incredible, are you kidding?

DBS: I think one aspect of the show that I keep thinking about is how the show is joined by three different ideas of the anthropocene and I really like how you ended when you walk through the exhibition,–listener, if you’re listening out there–you walk through the first [section]…

MP: …reconfiguring nature…

DBS: …and the second is…

MP: …toxic sublime…

DBS: …and the third…

MP: …inhumane geographies…

DBS: …and then and there’s the fourth…

JM: …envisioning tomorrow…

DBS: …and envisioning tomorrow is where you end in the exhibition. Today we did this walk through and we got to hear some artists speak and the curators spoke and it’s nice because we move through the spaces and spend more time than you may–well, I guess if you’re alone visiting you may spend a lot of time depending on how you look at art shows or museums but there’s no right or wrong way to do it–but it’s really nice how the exhibition ends in this envisioning tomorrow idea which for so many years–I was telling Marshall earlier–working on this project for myself it was a lot about survival in a way, thinking about preservation and thinking about landscape and what’s left of our landscape and how it’s hard not to go fumbling into the world…we’re doomed. Because I do think humanity may be doomed but I believe Earth will keep spinning and I think that having that–it may not keep spinning–but I do think that like there’s the power of nature that is above us all. It persists and it moves so much bigger than we do and we’ve become really smart or stupid and we’re merging with technology and all these things and it’s really easy to get lost in this idea of climate grief which is something that I really struggle with and I struggled with for the last decade/15 years. I photographed this beautiful tree on the coast of California one of the most beautiful trees i’d ever seen and I just photographed it and it was like just on the edge of this beautiful cliff above the Pacific Ocean near Big Sur and I just loved this photograph–printed it, it was by my bed. Then I do this thing where I kind of rephotograph my own photographs, sometimes I just like to go back and visit places and try a new perspective of it but also it’s comforting to see the rock or the mountain or the waterfall…and the tree within 2 years was gone and I was like in tears I was really…

HMB: …it’s like visiting a friend or a family member and it sort of puts a little puzzle piece in your heart.

DBS: Yeah, and there’s like this loss and like this this climate grief kind of came up for me I was like whoa It’s really happening and the photographs are like the remnants of what we can tell everyone what’s happening and I think that’s a lot of weight to bear. For some photographers it’s not they’re just like they go out into the world and they just take the picture and they move on and they’re in it and they’re living through it. But I think someone like myself who has this really deep personal connection to the natural world and my artwork is extremely personal it’s very emotional and I think that there’s something really beautiful in some of the works in that last room. Gohar Dashti’s photograph, I didn’t know anything about the artist I didn’t know much about the work, and just kind of walking through this show of all these different ideas but to see nature kind of taking over our spaces what we call our quote our spaces is like our our homes our apartments our if we’re lucky enough to live in a home and apartment, just that nature will continually move past us. I feel like also the really large scale Laura McPhee–who I’m such a fan of–and just such beautiful as an American Western photographer like her work always comes up for me especially when I speak to students because it’s incredible to experience that work. It’s like this beautiful photograph really large scale of the remnants of a wildfire in Idaho. There’s something that photograph of this full life takeover of this natural domestic space in the first two photographs of the artists that you mentioned before and then this burnt out huge massive photograph of these burned trees. You just think about life and death and regeneration and that cycle of what we’ve done, what we’re doing, what’s happened, what’s going to happen. But I think there’s something actually grounding in knowing that like the Earth is going to…I mean it WILL shift it’s shifting like the glaciers are melting, the sea rise all these things will happen…

HMB: …it will evolve adapt and become something new.

DBS: For me the hardest part about it is not humanity, we are destined to go we should go we should be gone, but the hardest part is a loss of entire ecosystems. For me as an artist that’s the hardest thing. The tree that fell off the cliff that I photograph that was painful to see because I’m like “wow this is really happening.” 10 years ago I was really clued into, in real time, what’s happening in the world in the natural world, but to hear of species of animals that are [disappearing] that, to me, is the most heartbreaking part of what’s happening in the anthropocene is wildlife being you know destroyed and the loss of…

HMB: …it’s happened before though, extinction. We’re up to the sixth extinction…

MP: …the seventh might be our own.

DBS: There’s something uplifting in that. I think it’s easy to get lost in the like this traumatic thing we’re living through but at the same time like it’s going to be okay.

HMB: I think in my work like it’s showing that it does move on, you know, the apocalypse happened in my work in one of those generations, but the land persists and us, as the custodians of the land, and belonging to the land, we also persist. We may not be in our numbers that we were, but our existence is…it’s a miracle really.

MP: I was just going to say that one of the small details in Laura McPhee’s photograph that’s so meaningful that often gets lost unless you get right up to it and look at it very closely are these wildflower buds in the foreground. It is a scene of destruction, to be sure, but also, and maybe most meaningfully, it’s the scene of renewal.

DBS: A what a powerful picture to end this whole journey through the exhibition. Curatorially, I just think it was really meaningful seeing that’s what you kind of leave with, these little buds of new life that will form and that’s what we’re left with. We have to change we have to shift–it may be too late–but also what a crazy wild time to be alive and to be witness to what’s happening in the world. I think as artists grappling with the anthropocene specifically it’s really a powerful show. I’m just so glad it’s also traveling because I feel like these are the types of shows that can really help a lot of people understand what these times are that we’re living through–especially young people–who feel like so lost and they’re like the world’s ending. But the truth is it’s like it’s a little hot out there but you can still get outside and it’s still beautiful. That’s all we can do is; go experience it, go outside and clean up your mess try not to waste, know your local farmers if you can if you can afford that, grow your own food if you can somewhere in a window sill anything. That is the only solution. Operate small, try not to fly much, things like that.

JM: Tatiana Schlossberg wrote a lovely little piece about the catalogue and she wrote if you don’t pay attention to the artists you won’t have a context for understanding the way that we are coming to live and I thought that was a beautiful way of thinking about that. And I think as we conclude this conversation I just feel really grateful not only to have the opportunity over these past years to be thinking about your work, you know, seeing it on my computer screen and seeing it when we visited studios and seeing it in the catalogue and now seeing it on the walls and then having the experience of you all bring not just the work to life but the entire lived experience that’s allowed you to create the work feels like a very special experience. So that’s what I’m going to take with me with much gratitude.

DBS: I think for us too–I mean not to speak for you–I also feel like as artists these ideas that you put into this show and the curation of it I’ve been wrestling with for 12/15 years as soon as I started taking landscape pictures it concerned a whole other part of this understanding of what’s happening in the world and I just I wasn’t sure I’m like I hope there’s museum shows one day that are talking about the anthropocene. Now, luckily, there’s more artists than there were dealing with this and coping with it and trying to understand it so I’m also really grateful that you see this in my work and that my work found you all and that we got to experience it and we got to all meet each other here and sit with this show and hope that it reaches tons of people in a really kind of positive way because that’s all we can do, right?

MP: Thank you. Thank you.

JM: Thank you so much.

DBS: Tank you all too.

HMB: Thank you.

DBS: See you in space! Just kidding, don’t ever. I’m not anti Earth, I’m pro Earth.

HMB: You’re not going to go to Mars?

DBS: I’m not going to Mars. I’m going to stay right here this is where it happens.